Terminological introduction

iv.1.1In a single-language dictionary, the following entry might be entitled “versification” or “prosody.” Given that “verse” in English does not correspond to the German or French Vers/vers, and that “prosody” has not established itself internationally as an all-encompassing term, the authors chose to focus instead on the following concepts: rhythm, metre, and line.

Rhythm

iv.1.2The term “rhythm” (from Greek ῥυθμός, rhythmós, etymologically derived from ῥεῖν ‘to flow’ by most scholar, for a notable exception see Benveniste 1966, 327–333) in its narrow sense relevant here denotes the perception of structured time by the recipient based on sensorily perceived events. These events are primarily acoustic (e.g., the beat of a drum or the sound of ocean waves), but can also be visual or tactile (such as a dancer’s motions or felt pulsation) (see Chatman 1965, 18–29; Arndt and Fricke 2003, 301–304). Rhythm does not necessarily imply isochrony (identical units of time between similar events), though it often goes along with it (see Winslow 2012, 1118). Indeed, isochrony is a result of a range of perceptual patternings known as gestalt laws. The meaning of “rhythm” thus can also be translated into the impression of salient time gestalts (see Mellmann 2008). In lyric studies, a poem’s rhythm refers to the perceived patterns (gestalt qualities) of a text’s prosodic features (pitch, duration, loudness, juncture). The terminological distinction between “rhythm” and “metre” is not a stable one: sometimes “rhythm” is used equivalent to the poem’s “metre” (see below ¶4–8); sometimes it rather means a rhythmic structure as opposed to metre: for example, “rhythm” may refer to the individual realisation of a given metre, to the sequence of accents in non-accentual metrics, to the temporal scansion of a poem, or even to musical patterns (see Beltrami 2011, 17–20). The reference point for Latin and subsequent traditions of Western poetics is Ancient Greek poetry, which was originally oral, either recited or sung, and generally accompanied by music (even for certain recited forms) and often by dance (especially in the case of sung poetry, see song and song-like). Poetic rhythm thus combined and enhanced speech rhythm with the rhythm of music and dance. Even the linguistic terminology of poetry, such as “prosody” (Greek prosodia, originally the musical part of song) or “accent” (derived from Latin ad-cantus), still reflects the original context of singing, and the rhythmic qualities of speech and music continue to influence the perceived rhythmicality of poems even when poetry is no longer performed or sung but read.

iv.1.3“Rhythm” is terminologically broader than “metre”, since it covers phenomena beyond linguistic features and signals a general human capacity or refers to temporal and perceptual patterns rather than to a culturally or historically defined instance of literary form. While folk theory claims that speech rhythm originates in embodied experience such as breathing, walking, or (unperceived) heartbeat, the actual emergence of the rhythmic faculty in humans, probably a multi-component phenomenon, remains largely unknown to date (see Fitch 2012). Therefore, radical extensions of the concept of rhythm are also conceivable, such as those proposed by Meschonnic on the basis of Benveniste (1966), where rhythm is a general term of poetic interpretation and denotes the organisation of the movement of ‘speech’ (“l’organisation du mouvement de la parole dans l’écriture”, see Meschonnic and Dessons 1998, 43).

Metre

iv.1.4“Meter is organized rhythm,” as Steele (1999, 3, emphasis in original) puts it succinctly. That is, metre is the series of rules governing the composition of a verse text, within which rhythm is developed (see Beltrami 2011, 18). In a broad sense, poetic “metre” (from Greek metron and Latin metrum, ‘measure’) comprises all formal schemata that, on several levels (e.g., syllable, feet, line or verse, stanza, poem), underlie a poetic text – whether intentionally drawn on by the author or extracted retrospectively. These schemata typically describe rules (along with licences of departure) for syllable placement, caesurae, lengths of sequences and their arrangement, and markers of opening and closure. In a narrow sense, “poetic metre” specifically refers to the predefined pattern of a single line (or sometimes two lines, such as the elegiac distich, or more, in the case of stanzas and strophes).

iv.1.5The units of metrical patterning are determined by the cardinal prosodic features of the respective languages. Thus, metrical systems differ among languages. One typically distinguishes systems based on syllable count on the one hand (syllabic metre) and systems based on syllable weight on the other. The latter can be instantiated either by syllable quantity (i.e., the length of syllables) or stress (i.e., word accent), which adds the metrical systems of quantitative metre and accentual metre to syllabic metre. However, historically realised metrical systems often show combinations of those theoretically distinguished systems (for instance accentual-syllabic verse in English; for further details on specific metrical traditions see below section 2). Moreover, the poetries of some languages do not focus on syllables at all but rather on tonality (pitch) or the syntactic structure of lines (for instance, parallelism in Hebrew).

iv.1.6Borrowing from ancient Greek-Latin models, line metres can be classified by the number and kind of subunits they contain: e.g., “hendecasyllable” (‘eleven syllables’), “iambic pentameter” (‘five iambic feet’, a cross-language list of terms can be found at the end of this article under ¶67). However, metre names often simply refer to a historical model (e.g., French alexandrine after the medieval Roman d’Alexandre) or to some characteristic feature (e.g., “blank” in English “blank verse” refers to its being ‘unrhymed’). Stanzas are basically classified by their number of lines: distich, tristich, tetrastich, pentastich; or also: couplet, tercet, quatrain, quintain (however, sestain or “sestet” denote a six-line complete poem rather than stanza). More complex stanzaic forms are defined by the regular and fixed succession of a certain type of verse or structured groupings of verses (e.g., monorhyme quatrain of alexandrines; in Spanish, cuaderna vía, pareado; in Italian, terza rima, ottava rima).

iv.1.7Though primarily defined by structural features, poetic metre is not an instance of form alone. In archaic Greece’s oral traditions, different occasions required specific types of poetry and, as poetry was closely linked to music, consequently specific types of metre. There is an ethos of metre (as well as of music). Using the smallest foot units as examples, iambs (from Gr. ἰάπτω ‘to hurt, send, rush’) and trochees (from Gr. τρέχω ‘to run’) are characterised by speed and levity, dactyls and anapaests by dignity and solemnity, spondees by gravity. Such traits are amplified and refined in larger structures. Thus, metre, together with subject matter and level of style, is linked with poetic genre, and tradition creates metrical norms (e.g., epic and didactic poetry use the dactylic hexameter; invective or dramatic dialogue use the iambic trimeter; etc.). Therefore, metres convey semantic and stylistic associations. They can be reused with effects of analogy or contrast, as is the case of the dactylic hexameter in Hellenistic pastoral poetry or in Roman satire (through epic parody).

iv.1.8In connection with more complex units (strophe, laisse, chapter or any other iterated structure, such as the octosyllabic couplet and the terzina), a set of terms derived from the word “metre” is used to describe the degree of regular organisation of their structure: The adjective “heterometric” is applied to a text or stanza with a regular structure but with verses of different lengths (e.g., the classic Petrarchan song with stanzas alternating hendecasyllables and septenaries), while the adjective “isometric” (or “homometric”) is applied to a text or stanza with verses of the same measure. In a tendentially regular structure, “hypometric” or “hypermetric” verses are respectively shorter or longer than the regular measure. Finally, a text consisting of stanzas with variations of metrical structures or an irregular structure is called “polymetric”.

Line

iv.1.9“Line” is a metrical unit that differentiates verse and poetry from prose. Although the emergence of the term in the English language in the second half of the 16th century is closely linked to the spread of print culture (see Brogan and Cushman 2012, 801), the term is more generally used for metric and structural organisation. In fact, the ancient Greek word for line is stichos, which means ‘row, file’, and more specifically ‘line of soldiers’: it also conveys the idea of walking forward, marching in line. Thus, the original meaning is not that of the line on the page (which makes no sense in an oral culture), but of successive items that mark the progression of the poem; it is especially significant for recited poetry, which moves ahead in mostly stichic metres (κατὰ στίχον, katà stichon, i.e., ‘line by line’). The term versus, from the Latin verb vertĕre ‘to turn, to go back’ i.e., ‘to start again’, marks the distinction from oratio prosa (prōrsum or prōsum, ‘straight’, hence ‘prose’). Italian verso, French vers, German Vers, etc., are derivations. In English, “line” is the usual equivalent to Latin versus, whereas “verse” is rather used for metered poetry in general on occasion as a dismissive term for cheap rhymes, or, rarely, for “stanza”. Similar to Latin versus, also the Greek term strophe builds on the idea of circular movement, but on a larger scale (more than one line), since strophe refers to (re)turning sequences of different lines, following the movements of the singing and dancing chorus in Greek performances.

iv.1.10Lines (as well as stanzas and strophes) are metrical units and do not necessarily coincide with syntactical structures: enjambment is regular in some verse types but rare in others. In Greek Antiquity, a line was originally defined by prosodic continuity (synapheia, which ‘binds together’). Within it, a word’s prosody may be affected by the neighbouring syllables; there is a break at the end of the line (which does not necessarily imply a pause in delivery). In Greek song, a line, according to this definition, can extend without prosodic break to a relatively large number of syllables (up to 40); for such cases, one prefers the term “period” (one such “line” would hardly represent one line in written text). Historically, the most important subdivision of the line is the colon (‘member’, pl. cola). As opposed to foot and metron (pl. metra), colon is a somewhat larger feature (5–12 syllables) that is not only rhythmical but can also coincide with a group of words (e.g., a dactylic hexameter is originally composed of two cola and arranged around a central caesura). Regular lines, along with less regular ones, have been retrospectively analysed in terms of feet or metra, theoretical units that do not account for caesuras, among other things.

iv.1.11In the oldest texts written in Romance languages, where the phrase coincides with the verse or with the couplet, a correspondence exists between metre and syntax. Most probably this correspondence also characterised oral poetry, facilitating the recognition and distinction of verses. However, some of the earliest French authors (e.g., Chrétien de Troyes) already break the coincidence between metre and syntax by adopting the brisure du couplet (i.e., two lines coupled by a rhyme that do not correspond to the syntactic structure), a technique that will later be generalised in the form of enjambment, which introduces an asymmetry between syntactic and metrical segmentation.

iv.1.12Another possible and important element is the homeoteleuton (rhyme or assonance), which contributes to delimiting the verse (also known as homoeoteleuton or homoioteleuton, from Greek homoio-, ‘similar’ and teleuté, ‘end’). In oral poetry, as well as in the oral performance of a written text, the homeoteleuton has long constituted the main element for recognising the end of a verse, as well as being a mnemotechnical aid for the performer. With the disappearance of the systematic use of the homeoteleuton, the recognition of verse is entrusted to rhythmic scansion and cadence, in particular the rhythmic break that characterises the end of the verse and to a lesser extent the possible internal caesura.

iv.1.13The typographical convention of delimiting a line by a line break has developed into a secondary determinant of the poetic line in Modernity. In contrast, in medieval manuscripts, the line is almost always marked by one or more elements: a space, a metrical point (i.e., a dot that marks a metrical unit), a capital initial, or a line break. From the earliest printed books, the typographical a capo or accapo (i.e., the convention of placing a line break at the end of a line) becomes the dominant form of delimiting and separating verse. Especially in so-called free verse (see below ¶62), sometimes only the typographic line breaks can tell how to delimit units of versification.

SUBJECT IN CONTEXT

iv.1.14The conventions and terminology of metrical analysis differ among languages and literatures. Although changes in prosodic forms and designations as well as moments of mutual influence can be found in the course of literary history, each language requires particular approaches to its prosodic characteristics. Ancient Greek and Latin, Romance languages, English and German are described in more detail below.

Metre in Greek and Roman Antiquity

iv.1.15Ancient Greek and Latin, like other (especially ancient) Indo-European languages, have in common two prosodic features that distinguish them from later traditions with regard to speech rhythm and poetic metre: the opposition between long and short vowels as well as syllables, and the melodic (i.e., pitch), not dynamic (i.e., stress) quality of the word accent, which is independent from rhythm. Consequently, rhythm in Antiquity is mainly perceived as the alternation of long and short syllables (i.e., vocalic quantity) and is independent from word accent: a syllable can be short and accented, or long and unaccented, or vice versa.

iv.1.16In Greek and Latin, a syllable is “short” if it has a short vowel and if it is open, i.e., if it ends with that short vowel; a syllable is “long” if it has a long vowel or a diphthong or, regardless of the length of its vowel, if it ends with a consonant. Although in actual speech the real duration of syllables may vary notably, in poetry a short syllable counts as 1 mora (minimal time-unit) and a long syllable as 2 morae. Thus, there is a conventional equivalence between one long syllable and two short ones, in much the same way as in music two eighth notes equal one quarter note. Depending on the metrical form, one long syllable can often replace two short ones (contraction), or two short syllables a long one (resolution). The final position of a line or period is always indifferens, i.e., can be realised either by a long or a short syllable.

iv.1.17In classical Antiquity, the alternation of strong and weak beats is one of quantity, not intensity (even though there could be a light, non-accentual stress on the strong beat); this changed later, already in late and medieval Latin, and particularly when the same basic feet were adapted and reinterpreted in accentual systems such as English or German. In ancient Greek and Latin, the word accent is (originally and for a long time) melodic. Since melodic accent can fall on weak as well as on strong beats, its prosodic line sometimes contrasts with the line of rhythm (heterodyny) and sometimes enhances it (homodyny).

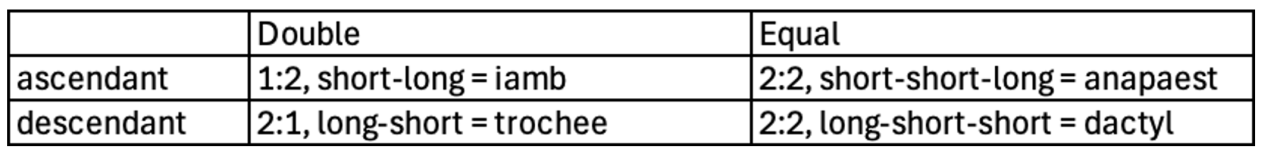

iv.1.18The sequences of syllables (feet) most frequently used in ancient Greek and Latin poetry have a ratio of morae that is either double (1:2 or 2:1) or equal (2:2), and their rhythm is either ascendant (weak-strong, i.e., short-long) or descendant (strong-weak, i.e., long-short):

iv.1.19Poetic forms employ particular metres depending on whether they are intended for recitation or for (originally) sung poetry. Recited poetry mostly uses homometric, “stichic” metres, in which one and the same line type recurs throughout the piece (the elegiac distich and epodic forms, i.e., small strophes of two lines, were most probably also recited, not sung). Two great families of recited poetry can be distinguished, the dactylic poetry (with the stichic dactylic hexameter as main form) and the iambo-trochaic poetry (with the iambic trimeter as most notable form).

- iv.1.20

- Most important in Greece and Rome is the tradition of dactylic poetry. Its main form is the stichic dactylic hexameter (originally formed of two cola around a central caesura but already perceived as a sequence of six metra in the 5th cent. BC). This panhellenic metre is used in the entire Greek and Latin epic tradition (beginning with the Homeric poems), in most didactic poetry (Hesiod and his followers), and later in pastoral and other genres (e.g. satire and poetic epistle in Rome). In the small strophic form of the elegiac distich or couplet, mainly used at symposia (elegy) and in inscriptions (later in epigrams), the dactylic hexameter alternates with the so-called pentameter (the latter may appear to have six feet, but more precisely it consists of two half-lines of 2½ feet, with a central caesura).

- The other main tradition of recited poetry, iambo-trochaic, has as its most notable form the stichic iambic trimeter (three iambic metra, i.e., three pairs of iambs), first used at Ionian and Attic symposia in diverse types of poetic exchanges. One of its variants, the scazon or choliamb (‘limping iamb’, because of a long at the place of the last short syllable), is especially suited to invective. As linked to conversation, the iambic trimeter is also the metre of the spoken parts of ancient drama. Ionian symposiac poets also use small strophic structures called ‘epodes’, with generally an iambic trimeter or a dactylic hexameter as their first line, and a second line composed of one or two shorter iambo-trochaic or dactylic cola.

iv.1.21Sung poetry presents a great diversity, but two main traditions are preeminent. While Aeolic poetry is rather “monodic” (sung by one performer), the Dorian tradition is mainly choral.

- iv.1.22

- The Aeolic tradition, first represented by the poets of Lesbos Sappho and Alcaeus, uses simple stanzas of 2–4 periods. This tradition is probably the most archaic one, with no contraction or resolution, a fixed number of syllables, and often undefined quantities at the beginning of the lines. The lines always contain at least one choriamb (long-short-short-long) and a clausula (of at least one syllable), most often also an “aeolic base” at the opening. As base and clausula can be reduced or extended, and the choriamb may be repeated once or twice or extended by one or two dactyls, different types of lines are combined to form different types of small stanzas (e.g., the Sapphic and Alcaic stanzas).

- The Dorian tradition, with Pindar as its main poet, is characterised by long and complex structures, combining various kinds of cola in unique strophic designs. Strophes often appear in groups, especially in “triads” formed of a strophe and an antistrophe of the same metrical shape, followed by a shorter variation called “epode”. This tradition is the model for most choral parts of tragedy, which, however, have no triads, but different pairs of strophe and antistrophe, sometimes with an epode at the very end.

iv.1.23Latin poetry is Greek poetry in Latin with the sole exception of the archaic saturnian verse (e.g., Livius Andronicus, Naevius, or early inscriptions). From Ennius onward (2nd c. BC, in a Hellenising context), only Greek metres are used and adapted to the Latin language. Latin versions of all the main Greek metres appear, except for the complex strophes and triads. Sung sections of drama too are different, generally varied but less formalised. In iambo-trochaic lines, Latin poets increase the possibilities of substitutions as well as of coincidence of strong beat and word accent by transforming the Greek iambic trimeter into a senarius (six iambic feet, with anceps and resolutions in the five first), and transforming tetrameters into octonarii or septenarii if catalectic (i.e., shorter by one syllable); Senecan tragedy, however, later returns to the stricter Greek practice. In late Antiquity, when quantity disappears, one finds accentual versions of the classical metres, but the form which gains most popularity is the iambic dimeter of Ambrose and Christian hymnody.

Romance metrics

iv.1.24Romance metrics are linked to the fundamental evolution that took place in the Latin language, from which all Romance languages derive. The earlier distinctive value of vocalic quantity was replaced in the 3rd and 4th centuries AD by a new qualitative phonological opposition of accented (“tonic”) and unaccented (“atonic”) syllables. This marks the transition from a definition of verse based on an isopodic structure (a certain number of feet consisting of two or more syllables one of which is marked by an ictus, Latin ‘beat’ for a stress) to one based on an isosyllabic structure (a certain number of syllables, regardless of the number of accents and feet). In their respective preference between choosing syllables or feet as the basic unit, Romance and Germanic languages (for English and German, see below) articulate their foremost prosodic differences.

iv.1.25All verse forms used from the very beginning in Romance literature are essentially derived from Late Latin rhythmic lines, which are themselves a rhythmic adaptation of Classical Latin metres. While the correspondence is not always perfect, and certain discrepancies have yet to be explained, the direct derivation link between the two traditions is now established. In some cases a contact of the Medieval Latin and Romance traditions with the Arabic tradition must be taken into account (see Minervini 2003). Moreover, it is likely that the relationship between Classical Latin metrics, Latin rhythms and vernacular metrics is not always unidirectional, and that the formation of a new vernacular metric could also have influenced its contemporary Latin counterpart.

iv.1.26In the history of the emergence and evolution of Romance metrics, the Gallo-Romance languages (e.g., French or Provençal) have a fundamental role. Due to their precursory position and the prestige they quickly acquired, they inevitably became models for other Romance language traditions, and, subsequently, for further Western poetic traditions. The main verse forms adopted for centuries in the literary traditions written in Romance languages all have an early origin in the Gallo-Romance tradition, which offers their earliest chronological attestations. Later, the same verse forms were adjusted and adopted in the other Romance language areas at the time of the emergence of their respective literary traditions.

iv.1.27Two elements characterise the Romance metrical system in the Middle Ages: the systematic use of homeoteleuton (i.e., rhyme or assonance), with aesthetic but also metrical functions, and the elaboration of isosyllabic metrical structures. While the Romance system can also be defined as accentual-syllabic, the syllabic element is clearly prevalent and the accentual element is confined to the last portion of the line (the last tonic syllable may be followed by 0, 1 or 2 atonic syllables) and partly to the location of the internal caesura that characterises long verses. Isosyllabism, however, is a late acquisition, distinctive of a social group and a literary genre. There are various cases of hypermetric and hypometric verses, and even more cases of anisosyllabism (i.e., variation in the number of syllables per line or verse within a poem); however, anisosyllabism is rarely found in canonical works. The rigour of the system also varies depending on the geographical areas and literary genres; while it is almost absolute in courtly lyric, metrical fluctuations combined with assonance is a characteristic of Spanish verse. Various explanations have been proposed for this phenomenon, from the adaptation of Germanic metres to the influence of Visigothic folk metrics (see Miletich’s 1987 theory on the Cid). Despite the extent of the fluctuations, there is an evident attempt to conform to the main Gallo-Romance metres, understood as an ideal measure to strive for, although not perceived as binding (this explanation is extended to all Romance metrics by Gasparov 1996 [1989], 120).

iv.1.28In predominantly syllabic systems such as Romance languages, the concept of metre applied to a single line primarily defines the number of syllables it consists of (hendecasyllable for lines with eleven syllables or decasyllable for lines with ten). Although the names suggest a cross-linguistic system, the metrical realisations differ depending on the poetic tradition.

iv.1.29In Romance languages, particularly French and Italian, the line or verse is the fundamental metrical unit and the minimal element of versification. It is generally defined contextually with other verses, although single-line poems exist as well (e.g., Apollinaire, “Et l’unique cordeau des trompettes marines”; Ungaretti, “M’illumino d’immenso”). The distinction of verse forms, however, becomes increasingly blurred with the introduction of free verse (see below ¶62), which has no predetermined length, creates aggregations that cannot be traced back to the isosyllabic norm and often contains no caesuras or pre-established rhythmic patterns. The first French examples of free verse are found in Jules Laforgue, Arthur Rimbaud, Gustave Kahn, Francis Vielé-Griffin. Prose poems are a case apart (e.g., Aloysius Bertrand’s Gaspard de la Nuit and explicitly in Baudelaire’s Petits poèmes en prose; for Italy see Gabriele D’Annunzio, for Spanish poetry Juan Ramón Jiménez).

iv.1.30Another element that distinguishes Romance languages such as Italian and French from Germanic languages to this day is the different treatment of vowel contacts, which contribute to determining the number of syllables in a verse. Two consecutive vowels can count as two distinct syllables or as a single syllable. In “diaeresis” two adjacent vowels that belong to the same word are considered as belonging to two different syllables (e.g., the Italian poetic form prezïoso); in “dialepha” two vowels that are considered as separate belong to different words (e.g., the cases of ne il without elision in medieval French). However, two adjacent vowels may be contracted to one syllable. In this case, one speaks of “synaeresis” if the two vowels belong to one word (as in the common Italian form prezioso), and “synalepha” if the contracted vowels belong to two different words. In general, diaeresis is only possible if it is etymological, i.e., if the two vowels can already be found in the corresponding Latin word and they do not form a Latin diphthong (e.g., Italian prezïoso from Lat. pretiosum). Moreover, there can be no diaeresis with genuine diphthongs (for example in the French form roi from Lat. regem).

iv.1.31With regard to the historical process of line aggregation in strophic structures, in many cases models can be found in Late Latin rhythmic poetry. In particular, the link between the strophic structures of Provençal cansos (songs) and the paraliturgical Latin versus produced in the context of the abbey of St. Martial of Limoges has been emphasised (see Chailley 1955).

iv.1.32With the exception of alexandrine, the names of verse lines in Romance languages are derived from their number of syllables, counting up to and including the last tonic syllable. Gallo-Romance lines can be defined as a sequence of positions, the last of which is necessarily strong and the penultimate necessarily weak. In the traditions of paroxytone languages (i.e., languages that tend to put an accent on the penultimate syllable such as Italian), the last strong position is usually followed by an atonic syllable. For this reason, the transfer of verses from a predominantly oxytonic linguistic tradition (i.e., accent on the last syllable) such as Gallo-Romance to substantially paroxytonic languages such as Romanian, Castilian and Italian resulted in the addition of a final atonic syllable, so that for example the French décasyllabe (=10 syllables) corresponds formally to the Italian endecasillabo (=11 syllables). From a prosodic point of view, the initial freedom in the consideration of vocalic encounters within the line will give way to the canonisation of the form of the hendecasyllable by Petrarch.

iv.1.33The octosyllable (=8 syllables, probably derived from the Latin iambic dimeter) makes its appearance as early as the 10th century in texts such as the Passion of Clermont-Ferrand and the French Vie de saint Léger. The French octosyllabe, initially associated with religious, encyclopaedic and didactic literature, owes its enormous medieval success to the extension of its use to narrative literature, for long and short poems (roman, dit, lai). In other Romance literary traditions, the use of octosyllable is more limited and essentially archaic, rapidly losing importance as time goes by. In France, too, the end of the Middle Ages marked the decline of the octosyllabe, which was only reintroduced in the 17th century for a few minor genres. It was not until the 19th century that it re-emerged in great lyric poetry (Verlaine, Baudelaire, Apollinaire), until it became the most used verse after alexandrine in modern lyric poetry.

iv.1.34There is no agreement on the origin of the decasyllable (=10 syllables), although the most probable hypotheses trace it back to the Alcaic hendecasyllable or the Alcmanian verse. It is attested from the 11th century in texts such as the French Vie de saint Alexis and the Occitan Boeci. Initially used for epic and hagiographic poetry, it soon became the main verse from of lyric poetry, in particular due to its success in the Italian tradition and its canonisation in Dante’s De vulgari eloquentia and later in Petrarch’s Canzoniere, spreading to all Romance traditions and beyond thanks to the phenomenon of European Petrarchism in the 16th century.

iv.1.35Alexandrine owes its name to the Roman d’Alexandre by Lambert le Tort and Alexandre de Bernay (c. 1180), although its first attestation dates back to the mid-12th century Pèlerinage de Charlemagne. The alexandrine rapidly replaced the decasyllable in epics and later became one of the main verses in French poetry. Having fallen into disuse in the 14th–15th centuries, it was taken over by the Pléiade and eventually replaced the décasyllabe in lyric poetry and then in the theatre, becoming the preferred verse of the elevated style from the 17th century onwards.

iv.1.36Some verse forms take on a particular importance and diffusion in certain linguistic areas: this is the case, for example, of the alexandrine in France, the endecasillabo and settenario in Italy (the latter is essentially the only verse that can alternate with the endecasillabo in lyric song), the octosílabo in Spain, which is the traditional verse of Castilian epic but is widely used in all genres up to modern times (see for example Federico García Lorca’s Llanto por Ignacio Sánchez Mejías, where the octosyllable alternates with the alexandrine of French origin and the Italian hendecasyllable).

iv.1.37As far as non-lyric forms are concerned, the first types of verse aggregation (i.e., fixed sequences of lines forming a metrical unit) already known in the Gallo-Romance languages are quickly associated with specific literary genres that contribute to their characterisation: the assonanced laisse (later also rhymed) for the epic, the rhymed couplet of octosyllables for the long and short narrative, the monorhyme quatrain of alexandrines for the didactic, the stanza for the lyric (the laisse has a variable number of lines, the lyric stanza generally a fixed number of lines).

iv.1.38The functional and combined organisation of metres and rhymes in genre structuring can evidently vary in individual linguistic areas. For example, this is the case for the epic-narrative and didactic type of laisse, in addition to progressively increasing the length of lines (moving from the archaic form in octosyllabes to décasyllabe and finally to alexandrine), but also for sporadic cases of anisosyllabism in French literature, frequent small syllabic oscillations in Italian literature and large and notable fluctuations in Castilian literature. In Italy, the laisse (both with décasyllabes or alexandrines) of discursive poetry was soon to be replaced by Dante’s terza rima (also known as sirventese incatenato and used for the first time in Dante’s Divine Comedy) and above all by the ottava rima, a strophe of hendecasyllables with an ABABABCC rhyme pattern. Ottava rima was first used in Boccaccio’s Filostrato or in the anonymous Florio e Biancifiore, and would later become the preferred metre of the great chivalric poems of the 15th and 16th centuries. As popular metre of discursive poetry, it was later joined by the loose hendecasyllable (endecasillabo sciolto), first used by Ariosto and then extensively in 16th century theatre and in translations of classical poems until the 19th century. The rhyming couplet, originally linked to the laisse, takes the name pareado in Spanish literature, where it is used for short poems, and is characterised by syllabic fluctuations and the admissibility of assonance, which is strictly excluded in French literature. In France, the rhyming couplet of alexandrines will become the privileged metre of the great theatre of the 17th century.

iv.1.39In addition to the distinction in literary genres, the different metres may also indicate a socio-cultural distinction. The assonanced laisse, for instance, is considered a predominantly jester-type metre, while the monorhyme quatrain is tendentially a learned and clerical metre. It is precisely the monorhyme quatrain of alexandrines (probably derived from quatrains of Latin minor asclepiadeans) that will enjoy great success and widespread use in French literature and will give rise to the Spanish cuaderna vía, the main metre of the mester de clerecía (clerical literature) employed from Gonzalo de Berceo onwards. In Spanish literature, the sociocultural element is also present in the distinction between versos de arte menor (short verses up to and including octosílabo) and versos de arte mayor (long verses).

iv.1.40For lyric poetry, the first theoretical arrangement of the metres of the genre (song, ballad, sonnet) is found in Dante Alighieri’s treatise De vulgari eloquentia. The song (canso, chanson, canzone, see also song/song-like), of Provençal origin, is the type adopted for the highest themes, while the ballad, often provided with a refrain, is associated with a type of production considered more popular. The refrain is very rarely found in the production of Occitan troubadours, while it is more frequent in the texts of Galician-Portuguese poets.

iv.1.41The stanza of a lyric song is a combination of several lines that constitutes the metrical cell, but also the semantic, syntactic and musical unit of a lyric composition. It consists, according to Dante’s definition, of a first part (frons) generally divisible into two symmetrical parts (pedes) and a second part (sirma) divisible or not into two parts (versus), but the indivisible sirma will be made canonical by Petrarch. The stanzas of a song generally repeat the same metric and rhyming scheme. Passing through Dante’s and Petrarch’s codification, the lyric song essentially reduces verse types to just hendecasyllables and heptasyllables. The Italian heptasyllables (settenario), perhaps initially perceived as the half of an alexandrine, will later probably be perceived as related to the second hemistich of an hendecasyllable. As for the typology of the strophes, too, the initial experimentalism gave way to the more or less fixed codification established and practised by Dante and Petrarch and spread throughout Europe in the 16th century. In the 19th century, the classical model of the lyric song would be superseded by the introduction of the free song, as introduced by Giacomo Leopardi (irregular stanzas of variously combined hendecasyllables and septenaries and absence of a fixed rhyme scheme).

iv.1.42From the 14th century onwards, the canonical forms of song and ballad were flanked by new fixed popular forms that were generally short and often conceived in association with a musical melody such as the madrigal, the motet, the rondeau, the frottola and the strambotto.

iv.1.43With the decline of medieval forms from the 16th century onwards, there was a general revival of the short metric forms of classical Latin poetry, reinterpreted in a rhythmic key. In France, forms such as the Pindaric ode, elegy and epigram were particularly successful, but the sonnet remained in vogue until at least the mid-17th century. The sonnet itself, together with other ancient Romance forms, would then be revived during the 19th century until the break marked by the spread of free verse.

iv.1.44In Italy, too, the revival of classical metres began from the 16th century onwards, including the Pindaric ode due to French influence, a metrical form that would still be adopted by Giovanni Pascoli. In the 19th century, there was a tendency to imitate classical strophic structures, especially Horatian, which led to the so-called “barbaric metrics”, as introduced by Giosuè Carducci.

iv.1.45In Spain, alongside the enduring success of the cuaderna vía, there was the spread of the popular romance metre, made up of pairs of octosílabos with fixed rhyme (or assonance) in even verses. The distinction between versos de arte menor and versos de arte mayor then continues, with the latter substantially derived from Italian metrics and thus perceived as linked to a learned tradition. The Italian ottava rima, known as octava real, was particularly successful and used mainly in the Ibero-Romance area for epic poems such as Os Lusíadas by the Portuguese Luís de Camões and La Araucana by the Castilian Alonso de Ercilla.

Rhythm and metre in English

iv.1.46In comparison to other Western, in particular Romance, languages, modern English poetry after Geoffrey Chaucer (14th c.) should be understood as accentual-syllabic (in some traditions of metrical analysis also known as syllabotonic verse). The concept of “long” and “short” syllables, familiar from purely quantitative meters, does not do it justice. The precise counting of syllables, which is determinative in much Italian and French poetry, does not generally work in English (exceptions exist, as in the American Modernist poet Marianne Moore).

iv.1.47With the substantial changes from Old English to Middle and Early Modern English that took place over the course of the 13th and 14th centuries, English poetry changed from a purely stress-based mode to an accentual-syllabic mode. In English, accent is determined by the normal pronunciation of a word, stress by metrical emphasis. Since the structure of the English language also changed from ‘synthetic’ or inflected to ‘analytic’ or uninflected, word order became a primary means of organizing sense, and particles as well as pronominals, which are almost always weak-stressed single-syllable words, gained in importance (see Steele 1999, 10). The result of these transformations is the re-emergence of iambic feet (see below ¶48), this time perceived as the alternation of a weak and a strong syllable (or an unstressed followed by a stressed syllable) as the primary vehicle for organizing rhythm. While variations, substitutions (such as spondees in the first position of iambic pentameter lines) are frequent, the basic underlying pattern often resolves to iambic. Yet irrespective of the particular foot or metre that is prevalent in a line or a poem, rhythm is perceived in English as the structural principle that organises rise and fall, fixity and flux (see Hirsch 2014, 534). Rhythm gives the motion to the words that ride upon it. Rhythm by itself says as yet nothing about the length of a poetic line or its metrical structure. Rather, it insists on its own recursiveness and can appear in prose as well. Thus, parallel sentence structures in prose writing also employ rhythm to enhance structure and signal meaning without thereby necessarily becoming poetry.

iv.1.48Thus, if lines are considered as divided into “feet” (with each foot having one stressed syllable and either one or two unstressed ones), the name for the prevailing foot or pattern provides the basic organizing principle which becomes the general, though not exclusive, meter of the poem. Lines may contain variations in their feet, but a recurring pattern emerges. Feet can be iambic (unstressed-stressed), trochaic (stressed-unstressed), dactylic (stressed-unstressed-unstressed) or anapaestic (unstressed-unstressed-stressed). The number of feet in a line gives the name to the meter perceived as prevailing: it can be monometer, dimeter, trimeter, tetrameter, pentameter, and so forth. The most recognizable forms in English are the tetrameter, which dominates hymns, ballads, and folk songs, and the pentameter, which generally makes a coherent statement across all five feet, although it can divide into a two-stress and a three-stress segment. In some poets (see especially Milton’s Paradise Lost), the iambic pentameter is the governing pattern – providing both feet and meter – but line endings, which normally help determine the underlying metrical pattern of a poem, become irrelevant in the headlong rush of Milton’s utterances.

iv.1.49In English-language lyric poetry, too, rhythm and metre are interconnected. The accent determines which meter governs the lines (see above, a metrical foot is established by the presence of one, and not more than one, accented syllable), and the syllables between those accents are counted to fill out the respective feet. They can thus vary; there is, in general, no requirement for a particular number of syllables in a line since English-language poetry seeks to approximate natural speech. Nonetheless, to fulfil a metrical schema, sounds or syllables can also be omitted (elision, see also aphaeresis) or added (epenthesis). However, forcing an accent on a syllable that is not accented to match a meter (i.e., wrenched accent) is considered a mistake though unproblematic in folk songs, ballads, or the lyrics for show tunes.

iv.1.50Metre is the central structural poetic device that governs a line, and often an entire poem. Comparable to measures in musical notation, metrical units in a poem measure passing time, giving a sense of regularity to their sequence. The meter of a line is rarely made explicit; rather, one can imagine the metrical pattern as running above the line of words on the page. Again, if it were notated music, the individual units of meter would resemble the bars that (also) measure passing time.

iv.1.51Since metre, in its regularity, does not represent the varieties of actual speech (which are measured in stresses), a poem’s meter is in a kind of creative tensions with the words in the line that conform, or do not conform, or creatively work in counterpoint to, the metrical units of the line. Conventionally called “feet,” these metrical units, in English, as Kinzie (1999, 438) notes, always have at least one (but not more than) one strong beat, while variant feet such as spondees, pyrrhic and others (see above) can only be used as substitutions in accentual-syllabic verse.

iv.1.52In English- and German-language poetry, line is the most significant formal device. In metered poetry, lines structure the poem visibly on the page and suggest a pattern that is repeated. If lines end together with syntactic structures, they are called end-stopped lines; in contrast, the enjambment can metrically cover the syntactic structure.

iv.1.53In free verse, which dispenses with rhythm and meter, line is practically the only structuring device the poet can still use, making it even more significant. In the most general of terms, line is what distinguishes poetry from prose. In printed prose, line endings occur serendipitously based on print and typeface, while in poetry, lines are the result of the most deliberate choice a poet makes. In metered poetry, readers pay attention to lines because lines structure the distinction between end-stopped pronouncements – in which the line ending is coterminous with the sense of the phrase or sentence, often indicated by a strong punctuation mark – and enjambed pronouncements – in which the syntax and the sense play against the line-endings by disregarding them. If, for example, iambic pentameter lends regularity to both rhythm and meter, but if the syntax pays no attention to line-endings, the words pull the reader forward, headlong, ever deeper into the poem. John Milton’s Paradise Lost is the prime example of unrhymed iambic pentameter in English that routinely disregards the line ending as a structural device. The lively interplay between the line visible on the page and the sense rushing along helps create the vivacity of discourse. By contrast, Alexander Pope’s heroic couplets (iambic pentameter lines rhymed in pairs) create small, two-line quasi-epigrammatic units that delight in contrast, equilibrium, and finality of pronouncement.

iv.1.54If speech stress is the regular and governing device of a line, as is the case with some early English verse (and some modern attempts, for example by Seamus Heaney), then this so-called “strong-stress meter” (Kinzie 1999, 385) is regulated exclusively by the total number of stresses per line. Intervening, unstressed syllables are not counted, or are sometimes deliberately made irregular. The emphasis on stress, as Kinzie (1999) observes, tends to favour trochaic words and thus results in a noun-heavy rather than a verb-heavy style in English.

Development of German metre

iv.1.55German verse underwent similar changes as English in history. Old High German (8th-11th century) is supposed to have had first-syllable word accents. This would explain the alliterating metre in the few remnants of Old German verse, such as the Hildebrandslied (9th century). Middle High German (11th-14th century) presumably was an accent-based quantitative language that in its poetic metres regarded syllable quantity, but only in relation to stressed syllables (see Vennemann 1995). In the transition to New High German, the syllable quantity was lost, and poets seem to have counted syllables at best. Most of the vernacular lyric was tied to musical tunes in any case; and the guild art of Meistersang (‘master singing’) continued to use the traditional Töne (‘melodies’) of medieval poets, i.e., adaptations of the Romanic canzona which they called Bar (‘song’). The earliest concepts for a German poetic metre based on feet (such as the ancient Greek/Latin models) arose in the late 16th century (see Schlütter 1966, 76-90; Wagenknecht 1971; Breuer 1994, 154-172). In 1624, the publication of Martin Opitz’s poetics (Buch von der deutschen Poeterey, Opitz 1977) allowed a syllable-weight based scansion principle to establish itself as the ruling method (Hebung: stressed syllable; Senkung: unstressed). Opitz explained to his audience that where the ancient languages put long syllables, in German one has to place stressed syllables. Furthermore, by prescribing dichotomic feet (iambic, trochaic) he offered a conveniently simple metrical system. This is why almost all German lyric poetry of that period has alternating rhythms. The use of three-syllable feet was largely confined to individual experiments, until the dactyl (stressed-unstressed-unstressed) became important for imitating hexametric rural poetry in the mid-18th century. Moreover, Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock presented models for complex heterometric ode stanzas in German and thus opened the door to the diversity of metrical forms that characterises German poetry since the late 18th century.

Metrical systems across genres and cultures

iv.1.56As the foregoing examples from western literary history show, the prosodic qualities of languages to some degree determine the metrical systems for poetry in these languages. However, particular forms might use a principle different from the principle that underlies the majority of metrical forms in a language. For example, English folk songs may use a principle of stress counting only, dispensing with the syllable count that is normally combined with it in English poetry. Also, cadence figures, pause, or other than prosodic kinds of patterning (such as anaphora, syntactic parallelism, word count) might intrude into, or even dominate, a certain formal tradition. Beyond the level of basic prosodic constituents offered by a particular language, everything is possible. Fabb (2015, 74-113) has provided a list of different types of poetic metre from about thirty poetic traditions, among them: metres based on stress and syllable counting (e.g., Pashto Qasida, a Havasupai song, Cretan long lines, Dyirbal songs), metres based primarily on stress alone (e.g., Akkadian poetry, Hittite verse), metres based on syllable counting alone (e.g., mediaeval Welsh metre, Javanese poetry, Avestan verse, Malay quatrains, Quechuan song duels), metres based on syllable counting and parallelism (Sulawesi headhunting song, Toda songs), metres based on syllable quantity (Classical Arabic metre, Moroccan Arabic songs), metres based on morae without reference to the containing syllables (Japanese metre, Ponapean songs, Nanti chants), metres based on morae and syllable boundaries (Hindi metre, Punjabi long lines, Sanskrit verse, Somali metre, Tashlhiyt Berber couplets), metres based on syllable quantity and stress (old Finnish and Karelian poetry), and metres based on lexical tone (Chinese and Thai stanzaic poetry).

Homeoteleuton, rhyme, assonance

iv.1.57Homeoteleuton (rhyme or assonance) has characterised Romance literature from its origins, on the basis of its use from the 5th century onwards in Late Latin literature, from which Romance metrics are derived (for a particularly ancient example of the use of homeoteleuton, see Sedulius’ Carmen paschale). In this sense, Romance literature immediately differs from Old Germanic poetry based on the insistent use of alliteration. Early examples of rhymed proto-Romance texts are the poetic charms of Clermont-Ferrand and the Occitan Passion of Augsburg (10th century). In the Iberian sphere, rhyme is already found in the oldest Mozarabic kharjas as well as in the cantarcillo of Almanzor (11th century). Perfect rhyme is defined as the total identity of the sounds of the final part of two words starting from the last tonic or accentuated vowel in accentual-syllabic metre. The ancient Gallo-Romance tradition distinguishes between masculine rhyme (where the last tonic syllable is the absolute end of the word) and feminine rhyme (the last tonic syllable is followed by an atonic syllable), while in the Iberian and Italian tradition, where the use of proparoxytone forms is permitted, there can be single (oxytonic), double (paroxytonic) and dactylic (proparoxytonic) rhymes. By contrast, in less scholarly texts, assonance prevails, which is distinguished from rhyme by the only partial coincidence of sound material starting from the last tonic vowel, which tends to concern only vowels and not consonants. The basic form is flanked by other types of rhyme (derivative, grammatical, eye rhyme etc.), among which the equivocal rhyme (two words with the same sound but different meanings) and the rich or leonine rhyme (where the identity is extended to one or more sounds preceding the last tonic vowel) are particularly noteworthy.

iv.1.58Many hypotheses have been raised regarding the etymological origin of the word “rhyme”. Three prominent instances are presented here: the word rhyme would derive respectively from the Germanic rim ‘number’ (see Günther 1959), from the Latin rhythmus (see Zumthor 1975; Gasparov 1996 [1989]), or from the Latin rima ‘fissure’ (Antonelli 1998). It is particularly important to note that, in addition to its demarcative, aesthetic and mnemonic function, the rhyme soon assumed the role of bearer of meaning and, according to Jakobson (1960, 367), it “necessarily involves a semantic relationship between rhyming units”.

iv.1.59Sequences of rhymes are usually designated with alphabetical letters (e.g., abba for enclosing rhyme). Rhymes are usually classified according to position, quality, the repeated phonetic elements, the number of syllables involved etc. Please refer to the cross-language list of terms below for an overview of the forms.

International forms

Sonnet

iv.1.60Poetic and metric forms are frequently considered only in relation to specific linguistic traditions, whereas the history of metrics demonstrates continuous cross-linguistic influences. One of the most important contributions of Romance poetry is undoubtedly the stanzaic sonnet. It is considered an invention of the Sicilian poetic school (the oldest examples were composed in the first half of the 13th century and are attributed to Giacomo da Lentini) probably deriving from the tradition of the Occitan coblas esparsas (the model is in fact certainly that of a stanza from a lyric song). In its canonical form, the sonnet consists of 14 lines, almost always hendecasyllabic in Italy, more often alexandrine in France, divided into two quatrains and two tercets. Initially exclusive to Italian literature, the sonnet was first taken up in Spain in the 15th century and then, starting with Petrarchism in the 16th century, it enjoyed an immense European diffusion to become the most international and widespread of lyric forms, an almost emblematic representation of lyric poetry made illustrious, with variations on the original scheme, by the greatest poets of the different eras and literary traditions (Pierre de Ronsard, Garcilaso de la Vega, Luis de Camões, William Shakespeare, John Milton, Gérard de Nerval, Charles Baudelaire, Pablo Neruda).

iv.1.61In the English-language sonnet tradition, experiments with more rhyme words (teleutons) by Spenser and Sidney led to the development of what is now known as the Shakespearian sonnet, generally composed of three quatrains in iambic pentameter with alternating rhymes (abab cdcd efef) and a concluding couplet (gg). The volta thus moves to the end; the poem’s argumentative structure changes. Petrarchan, Shakespearian, Miltonic and other forms of the sonnet in English existed side-by-side in the Romantic and Victorian eras, with William Wordsworth, John Keats, George Meredith, Matthew Arnold and – innovatively – Gerard Manley Hopkins using and modifying the sonnet form (see the Penguin Book of the Sonnet, Phillis 2001).

Free verse

iv.1.62The rise of free verse during Modernity brought about a plethora of different styles of versification which can no longer be referred to by distinct terms and often lack systematic description. In the age of constrained metrical traditions, what was occasionally called ‘free verse’ in fact was a largely regulated but especially flexible kind of metre used in non-lyrical (i.e., narrative or argumentative) poems predominantly. Examples are the unrhymed Italian versi sciolti (also versi liberi), the classical French vers libres (also vers mêlés) or the German Madrigalvers (also vers libres/mêlés, or Faust-Vers). Only in the pre-Romantic and Romantic eras, explicitly and emphatically un-metrical verse was propagated as a way of lyric expression in its own right. The new German hymnic style as introduced by Klopstock’s 1759 ode Das Landleben, and retrospectively called Freie Rhythmen (‘Free Rhythms’) in German philology, is the most prominent example. It was meant to be an imitation of both biblical verse and Pindaric dithyrambs (Kohl 1990; Ronzheimer 2020, 21-77) and was adopted by authors such as Goethe, Hölderlin, and Nietzsche. Beyond avoiding stanzaic form, rhyme and regular metrical patterns, Freie Rhythmen are additionally characterised by frequent stress clashes (Hebungsprall), heavy enjambment and, more generally, by what Norbert von Hellingrath (1911, 1-25) has termed “hard jointing” (harte Fügung), as opposed to “smooth jointing” (glatte Fügung), that is, a style of diction based on rhetorical features such as inversion, exclamation, ellipsis, hypotaxis, neologism, and complex composita (Lyrical Style, Poetic Language, Stylistic Devices).

iv.1.63French Symbolism represents a second historical wave of free verse, with great influence on poets all over Europe. French lyrical studies usually distinguish between vers libérés on the one hand (e.g., Verlaine’s poem Art poétique, 1874, first printed in 1882), which merely extend traditional metres by more flexible rules of syllable counting and admitting assonance as an alternative to rhyme, and vers libres, or verslibrisme, on the other, which dissolves poetic metre into freely arranged rhythmic groups of varying length. Early examples are found in Rimbaud’s poems Marine and Mouvement (1873, first printed in Illuminations, 1886). Taken together, these two developments anticipate the great variety of European free verse between the 1870s and the 1930s which is best summarised as a trend to individualise the metrical form for each poem, ranging from slight alterations of traditional forms via rhythmic prose “haunted by meter” (Beyers 2001, 42-43) to reinventions of “Free Rhythms” and to experimental new ways of sequencing and patterning. A possible third wave of free verse is the programmatically prosaic poetry occurring in the second half of the 20th century that dispensed with any markedly literary style. All of these are instances of “free verse” in some poorly, predominantly negatively defined sense and, though useful typologies exist (e.g., Berry 1997; Beyers 2001; Wagenknecht 1999, 101-104), all of them require individual description and analysis.

iv.1.64Those individualised forms can still be described by means of traditional metrical analysis. This is no longer obvious for the ‘flow’ in rap music (and derived forms of recent poetry). Describing the flow as “loose, four-stress, end-stopped lines” with occasional wrenched accents and an emphasis on (extravagant) rhyming (Caplan 2012, 632) neglects the fact that the way in which the syllables are distributed over the four beats does not necessarily itemise into feet or foot-like units. The duple and triple rhythms that have been underlying traditional forms of rhythmically patterned speech (see Attridge 2012, 1196) tend to be overridden in rap. Though the four-beats “bar” is virtually divided into 16 or 32 subunits, these metronomical units do not strictly prescribe syllable slots (see Edwards 2009; 2013, 6-53). The art of rapping rather consists in conversational speech bursts that occasionally coincide with, or yield to, the musical beat but, in between, stretch or speed syllables, shift their boundaries against those of the metrical units, pause at main beats, etc. Accordingly, the resulting performance “to some degree reflects, to some degree deforms, both the natural rhythms of the language and the metronomic beat of the accompaniment” (Attridge 1995, 93). While borrowing from both linguistic rhythm and musical beat for its rhythmic organisation, the rap flow realises neither of them obligatorily but rather owes its rhythmicality to repeating patterns of (re-)combining them.

Topics for further investigation

iv.1.65In the second half of the 20th century, starting with the studies of Roman Jakobson, there has been an increasing inclusion of metrics within linguistic theory. Linguists posit that metrical forms can be treated as a coherent set of equivalence relations, or, as Jakobson (1960, 358, italics in original) put it, “The poetic function projects the principle of equivalence from the axis of selection into the axis of combination. Equivalence is promoted to the constitutive device of the sequence”. A further development of metrical studies concerns the concept of verse structure assumed by metrics inspired by generative grammar (see Halle and Keyser 1966 and 1971; Roubaud 1971; Di Girolamo 1976; Duffel 1999), which, starting from the non-correspondence between the counting of syllables in the language and in metrics, defines verses on the basis of the numbers of positions and ictus. Two main lines develop from these theoretical starting hypotheses: one that postulates an abstract model on which to base the equivalence relations of metrics (see Ruwet 1986) and one that limits itself to describing these relations in verse as it occurs (see Cornulier 1982). From these theories, various currents of metrical studies developed in different linguistic areas at the turn to the 21st century.

iv.1.66A question still open to further examination is whether there is something like a universal line length and, if so, by what psychological constraints it is determined. For example, Chatman (1965, 26) suggested a maximum of four to five seconds after reviewing several studies in rhythm in experimental psychology; Turner and Pöppel (1983) assumed a universal line of about 3 seconds that matches with the assumed auditory information buffer of the human brain; Tsur (1977; 1998; 2008) correlated the reader’s ability to structure verse with the seven (±2) chunks of information that George A. Miller in the 1950s (by analogy to telephone digits) estimated to be the approximate processing unit of short-term memory; similarly, Hogan (1997, 241-244) observed a cross-cultural span of five to nine words per line and tentatively borrowed from Miller’s theory. More recently, Fabb (2015, 173-179) has drawn on Alan Baddeley’s model of working memory to propose that metrical units generally have to fit into the episodic buffer of about four chunks or objects. Admittedly, all of the psychological models of working memory rely on heavily indirect evidence and are clearly speculative to some degree, and so are theories of poetic metre striving to correlate with them. Still, the general path taken by these approaches – asking for constraints imposed on verse by working memory and its buffers – seems a reasonable way to go, as well as the emerging consensus that added poetical form (time gestalts, rhythmical patterns) might be processed separately; that is, independently of the semantic processing (within the phonological loop, in Baddeley’s and other’s terms). While these theories do not lend themselves easily to direct testing, it would be good to identify more closely the perceived textual units that might correlate with a “chunk” in terms of cognitive psychologists. Eye tracking would perhaps be a plausible way to do this. Conceptualisations of different levels of how poetic subunits are integrated into larger sections are also required.

Cross-Language List of Terms

iv.1.67Please note that metrical terms may be translated even if they do not apply to the metrical system of a given language or have been re-interpreted within that language’s metrical system.

- iv.1.68

- accent (see stressed / unstressed; wrenched accent)

Ital.: accento; Fren.: accent; Span.: acento; Germ.: Akzent, Betonung - accentual-syllabic meter, syllabotonic, syllable-stress metre

Ital.: sistema accentuativo-sillabico, metrica sillabo-tonica; Fren.: syllabo-tonique; Span.: métrica silabotónica; Germ.: akzentuierendes Versprinzip - alexandrine

Ital.: alessandrino; Fren.: alexandrin; Span.: alejandrino; Germ.: Alexandriner - alliterative verse (alliteration)

Ital.: metro allitterativo (allitterazione); Fren.: versification allitérative; Span.: aliteración; Germ.: Stabreim - alternate rhyme (ABAB)

Ital.: rima alternata; Fren.: rimes croisées [not necessarily m/f], rimes alternées; Span.: rima cruzada; Germ.: Kreuzreim [not necessarily m/f] - anapaest (see metrical foot)

Ital. anapesto; Fren.: anapeste; Span.: anapesto; Germ.: Anapäst - aphaeresis (see epenthesis)

Ital.: afèresi; Fren.: aphérèse; Germ.: Aphärese - assonance (see homeoteleuton)

Ital.: assonanza; Fren.: assonance; Span.: asonancia, rima asonante, rima vocálica; Germ.: Assonanz - blank verse

Ital.: verso sciolto, verso libero; Fren.: vers blanc; Span.: verso blanco; Germ.: Blankvers - caesura

Ital. & Span.: cesura; Fren.: césure; Germ.: Zäsur - colon (cola, pl.)

Ital.: colon, Fren.: côlon, accent de groupe; Germ.: Kolon (n.), Wortfuß, Atemgruppe, Phrasierungseinheit - couplet (see distich)

Ital.: distico; Fren.: couplet; Span.: pareado; Germ.: Couplet, Zweizeiler - dactyl (see metrical foot)

Ital.: dáttilo, dattilico; Fren.: dactyle, dactylique; Span.: dáctilo; Germ.: Daktylus, daktylisch - decasyllable

Ital.: decasillabo; Fren.: décasyllable; Span.: decasílabo; Germ.: Zehnsilbler - diaeresis, dialepha

Ital.: dieresi, dialefe; Fren.: diérèse, dialèphe; Span.: diéresis, dialefa; Germ.: Dihärese, Diärese, Dialephe, Dialöphe - dimetre

Ital.: dipodia, dimetro; Fren.: dimètre; Span.: dímetro; Germ.: Dimeter (only for classical metres, else: zweihebiger Vers) - distich (see couplet)

Ital.: distico; Fren.: distique; Span.: dístico (only for classical metres); Germ.: Distichon (only for classical metres) - dodecasyllable

Ital.: dodecasillabo, evtl. alessandrino; Fren.: dodécasyllabe, evtl. alexandrin; Span.: alejandrino; Germ.: dodekasyllabischer Vers (only for classical metres, else: Alexandriner) - elision (see also synaeresis)

Ital.: elisione; Fren.: élision; Span.: elisión; Germ.: Elision - embracing rhyme / enclosing rhyme (ABBA)

Ital.: rima incrociata; Fren.: rimes embrassées; Span.: rima abrazada; Germ.: umarmender Reim - enclosing rhyme (see embracing rhyme)

- end-stopped lines

Germ.: Zeilenstil - enjambment

Ital.: enjambement, evtl. spezzatura, inarcatura; Fren.: enjambement; Span.: encabalgamiento; Germ.: Enjambement, Zeilensprung - enneasyllable

Ital.: novenario; Fren.: ennéasyllabe; Span.: eneasílabo; Germ.: Neunsilbler - epenthesis

Ital.: epentesi; Fren.: épenthèse; Span.: epéntesis; Germ.: Füllsilbe, Epenthese - eye rhyme

Ital.: rima all’occhio; Fren.: rime pour l’œil; Germ.: optischer Reim, Augenreim - free verse

Ital.: verso libero, Fren.: vers libre; Span.: verso libre; Germ.: Freie Verse - hemistich;

Ital.: emistichio; Fren.: hémistiche; Span.: hemistiquio; Germ.: Halbvers, Hemistichion - hendecasyllable

Ital.: endecasillabo; Fren.: hendécasyllable; Span.: endecasílabo; Germ.: Elfsilbler, Endecasillabo - heptasyllable

Ital.: settenario; Fren.: heptasyllabe; Germ.: Siebensilbler - hexametre

Ital.: esametro; Fren.: vers hexamètre; Span.: hexámetro; Germ.: sechshebiger Vers, Sechsheber (only for the classical epic hexameter and first line of the classical elegiac distich: Hexameter) - homeoteleuton (see rhyme or assonance)

- iamb, iambic (see metrical foot)

Ital.: giambo, giàmbico; Fren.: ïambe, iambique; Span.: yambo; Germ.: Jambus, jambisch - internal rhyme, middle rhyme

Ital.: rima interna, rima al mezzo; Fren.: rime batelée, brisée, fratrisée, enchaînée; Span.: rima interna; Germ.: Binnenreim - isosyllabic / anisosyllabic

Ital.: isosillabismo, isosillabico; Fren.: isosyllabisme, isosyllabique; Germ.: Isosyllabismus - line, verse

Ital. & Span.: verso; Fren.: vers; Germ.: Vers - meter, pattern of versification

Ital.: metrica; Fren.: métrique; Span.: métrica; Germ.: Metrik, Verslehre - metre, metron (or “meter” in American English spelling)

Ital.: metro; Fren.: mètre; Germ.: Metrum (n.), Versmaß - metrical foot (see also iamb / anapaest / trochee / dactyl / spondee; monometre / dimetre; trimetre / tetrametre / pentametre)

Ital.: piede; Fren.: pied; Span.: pie; Germ.: Versfuß - monometre

Ital.: monometro, monopodia; Fren.: monomètre; Span.: verso unípede; Germ.: Monometer, Monopodie (only for classical metres, else: einhebiger Vers) - octosyllable

Ital.: ottonario; Fren.: octosyllable; Span.: octosílabo; Germ.: Achtsilbler - pentametre

Ital.: pentametro, pentapodia; Fren.: pentamètre; Span.: pentámetro; Germ.: fünfhebiger Vers, Fünfheber (only for the dactylic pentametre in the second line of the classical elegiac distich: Pentameter) - prosody

Ital. & Span.: prosodia; Fren.: prosodie; Germ.: Prosodie - quantitative metre

Ital.: quantità sillabica; Fren.: quantité syllabique; Germ.: quantitierendes Versprinzip - quatrain (see also tetrastich)

Ital.: quartina; Fren.: quatrain; Span.: tetrástico; Germ.: Vierzeiler, vierzeilige Strophe (in sonnet: Quartett) - rhyme (see also internal rhyme / rhyming couplet / alternate rhyme / embracing rhyme / tail(ed) rhyme / eye rhyme)

Ital.: rima; Fren.: rime; Span.: rima; Germ.: Reim - rhyming couplet (AABB)

Ital.: rima baciata, distico; Fren.: couplet, distique, rimes plates, rimes suivies, rimes jumelles; Span.: rima pareada, rima gemela; Germ.: Paarreim - rhymeless line (in a rhymed poem, usually annotated with ‘X’)

Ital.: verso sciolto, rima irrelata; Fren.: rime orpheline; Germ.: Waise - rhythm

Ital. & Span.: ritmo; Fren.: rythme; Germ.: Rhythmus - spondee (see metrical foot)

Ital.: spondeo; Fren.: spondée; Span.: espondeo; Germ.: Spondeus, Spondäus - stanza (see also distich, couplet / tristich, tercet / tetrastich, quatrain / pentastich, quintain / terza rima)

Ital.: strofa; Fren.: strophe; Span.: estrofa; Germ.: Strophe - stressed vs. unstressed syllable (tonic vs. atonic)

Ital.: sillaba tonica vs. atona; Fren.: syllabe tonique vs. atone; Span.: sílaba tónica, sílaba acentuada vs. sílaba átona; Germ.: Hebung vs. Senkung - syllabism, syllabic verse metre (see also isosyllabic / dodecasyllable / hendecasyllable / decasyllable / enneasyllable / octosyllable / heptasyllable)

Ital.: sillabismo; Fren.: syllabisme; Germ.: silbenzählendes Versprinzip - synaeresis, synizesis, synalepha

Ital.: sinizesi, sineresi, sinalefe; Fren.: synérèse, synalèphe; Span.: synéresis, sinalefa; Germ.: Synärese, Synhärese, Synalöphe - tail(ed) rhyme (AABCCB)

Ital.: rima caudata; Fren.: rimes couées; Germ.: Schweifreim - tercet (see also tristich and terza rima)

Ital.: terzetto, terzina; Fren.: tierce rime; Span.: terceto; Germ.: Terzett (in sonnet) - terza rima (see also tercet)

Ital.: terza rima; Fren.: tercet; Span.: tercia rima, terza rima; Germ.: Terzine - tetrametre

Ital.: tetrametro, tetrapodia; Fren.: tétramètre; Span.: tetrámetro; Germ.: vierhebiger Vers, Vierheber (only for classical metres: Tetrameter) - tetrastich (see also quatrain)

Ital.: quartina; Fren.: quatrain; Span.: tetrástico; Germ.: Vierzeiler, vierzeilige Strophe (in sonnet: Quartett) - trimetre

Ital.: trimetro, tripodia; Fren.: trimètre; Span.: trímetro; Germ.: dreihebiger Vers, Dreiheber (only for classical metres: Trimeter) - tristich (see also tercet and terza rima)

Ital.: terzina; Fren.: tercet; Span.: terceto; Germ.: Dreizeiler (in sonnet: Terzett) - trochee (see metrical foot)

Ital.: trocheo; Fren.: trochée; Span.: troqueo; Germ.: Trochäus - verse (see line)

- versification

Ital.: versificazione; Fren.: versification; Span.: versificación; Germ.: Versifikation, - wrenched accent

Span.: acento extrarrítmico; Germ.: Tonbeugung

Austenfeld, Thomas, Luca Barbieri, Katja Mellmann, Olivier Thévenaz. 2026. "IV.1. Rhythm, Metre, Line." In Poetry in Notions. The Online Critical Compendium of Lyric Poetry, edited by Gustavo Guerrero, Ralph Müller, Antonio Rodriguez and Kirsten Stirling. DOI: https://doi.org/10.51363/pin.hc87.